This post introduces my chapter the Special 301 Report in the newly-published book Intellectual Property and Access to Medicines. The chapter, titled “Unilateral Norm Setting Using Special 301” focuses on Special 301 listings from 2009 to 2020 related to intellectual property policies that can be used to access generic medicines. This post will also describe the Special 301 listings in the 2021 Special 301 Report, which was released after the Covid-19 pandemic had taken hold. There were some differences in the 2021 Report pertaining to specific TRIPS flexibilities useful in the fight against Covid-19. However, much of the 2021 Report was similar to the reports released before the pandemic – the Report still criticized countries for policies that could help the fight against Covid-19.

The chapter is based on my Texas A&M University white paper on the subject, which is available here.

What is the Special 301 Report?

Each year, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) releases the Special 301 Report, which identifies countries that “deny adequate and effective protection of intellectual property rights or deny fair and equitable market access to U.S. persons who rely on IP protection.” USTR bases the Report on a review of trading partners, and it solicits input from industry lobbies. The Special 301 Report classifies countries according to the seriousness of their alleged shortcomings, placing countries deemed to have the most serious violations on the “Priority Watch List” or designating them “Priority Foreign Countries.” Other countries are placed on the “Watch List.”

The Trade Act requires USTR to produce the report annually. The law is worded in a way that encourages USTR to promote levels of intellectual property protection exceeding what is required by the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement). USTR must identify countries that deny “adequate and effective” protection of intellectual property, and the Act specifically states that a “country may be determined to deny adequate and effective protection of intellectual property rights, notwithstanding the fact that the foreign country may be in compliance with the specific obligations of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.” [19 U.S.C. § 2242(d)(4)]

Intellectual Property Provisions Related to Access to Medicines That Frequently Appear in Special 301 Reports

Special 301 Reports routinely criticize countries for TRIPS-compliant intellectual property laws that promote access to generic medicines. My chapter looks at four types of provisions, which I briefly describe below.

Pharmaceutical test data protection

Pharmaceutical manufacturers need to obtain marketing approval from health regulators to sell in most markets. Brand-name manufacturers submit clinical test data to regulators showing that the drug is safe and effective. Generic firms usually rely on the originator’s test data, allowing them to bring their products to the market at a lower cost.

TRIPS Article 39.3 requires companies to protect test data against “unfair commercial use.” In the U.S. and most other developed countries, this protection takes the form of data exclusivity – a period of time during which generic firms may not apply for marketing approval based on the originator’s test data.

Data exclusivity is a type of IP barrier to the entry of generic products to the market that is separate from patent protection. It has the potential to block generic entry in situations where a patent has expired or was never in force. In some developing countries, pharmaceutical firms may decline to apply for patents, but still claim exclusivity over the test data. Data exclusivity is the U.S.’s favored way to implement the TRIPS requirement of protection against unfair commercial use, and requirements for data exclusivity are included in all of the bilateral and regional trade agreements that the U.S. has negotiated since the 1990s.

There is no WTO rule mandating data exclusivity, yet the Special 301 Report regularly lists countries that do not provide data exclusivity for failing to adequately protect test data.

Patent linkage

Patent linkage refers to a mechanism for ensuring that health regulatory authorities do not approve a generic product for sale while an unexpired patent protects the drug or a mechanism to ensure that patent owners are notified when a generic manufacturer applies for regulatory approval to sell a follow-on product. In practice, systems of linkage have led to problems with follow-on patents (and patents of poor quality) delaying the entry of generics after the expiration of the relevant patent on medicines. Patent linkage is not required under the TRIPS agreement. It is required by most of the U.S.’s bilateral and regional trade agreements.

Scope of patentability

TRIPS requires patents to be made available for inventions that are “new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application.” However, countries are free to define what is new and what is useful according to their laws.

The scope of patentability varies from one country to another. Many countries have implemented strict standards of patentability to avoid granting patents on innovations that are not completely new, like second uses of existing medical products, or common derivatives of known substances. Some countries have different rules for biologic inventions, which may be simulations of substances created in nature. Other countries have relatively loose standards of patentability, making it easier for firms to patent variations to existing products.

It is U.S. policy to advocate for loose standards of patentability, so firms can patent a wide range of products. USTR lists countries in the Special 301 Report for alleged inadequacies regarding what a firm can patent.

Compulsory licensing

A compulsory license authorizes a third party to produce and/or sell a patented invention without the authorization of the patent holder. Compulsory licenses have been part of the international patent law landscape since the Paris Convention of 1883, and are permitted under Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement. The domestic laws of most countries have provisions for compulsory licenses, including the U.S.

Domestic laws typically allow compulsory licenses for a variety of public interest purposes, including (but not limited to) meeting public health needs. They often establish mandatory conditions for the issuance of a license, such as payment of royalties to the patent holder. The specific details of compulsory licensing policies vary from one country to the next.

Many countries have issued compulsory licenses for medicines since the 1990s. Many, but not all, of these licenses have been for AIDS and cancer treatments. The U.S. government has a history of opposing the issuance of compulsory licenses for medicines, through listing in the Special 301 Report as well as other means.

Trends in Special 301 Listings Related to TRIPS Flexibilities Useful for Access to Medicines

My chapter in Intellectual Property and Access to Medicines looks specifically at countries that the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) asked USTR to include in the Priority Watch List, the Watch List, or to identify as a Foreign Priority Country for each of the years from 2009 through 2020. The chapter looks at three types of complaints – complaints about the use of TRIPS flexibilities, complaints about inadequate enforcement of IP rights, and complaints about market access barriers that are not concerned with intellectual property. This blog focuses on complaints related to the use of TRIPS flexibilities.

It finds that “approximately 75 percent of countries identified by PhRMA and listed by USTR were criticized each year for using TRIPS flexibilities. Variation by year ranged from a low of 63 percent in 2009 and 2013, to a high of 88 percent in 2010. In 2020, USTR cited 82 percent of these countries for using TRIPS flexibilities.”

Most of the countries listed for the use of TRIPS flexibilities are middle-income countries, and most have large populations. India and China are always included on the list, but so are other large middle-income countries, like Indonesia. More than half of the world’s population resides in countries identified by PhRMA and subsequently listed by USTR in the Special 301 Report.

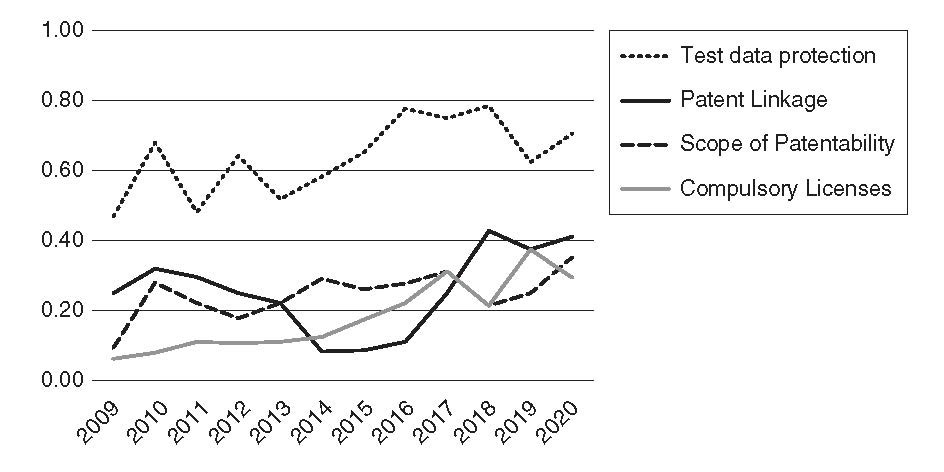

The figure below, taken from my chapter, shows the percentage of times specific policies were cited in Special 301 country listings (out of the set of countries that were identified by PhRMA and subsequently included in the Report each year).

FIGURE: Frequency of TRIPS flexibilities cited in countries identified by PhRMA and listed by USTR (%)

Lack of data exclusivity – or incomplete data exclusivity – was the most frequently criticized. Each year, USTR cited between 47 percent and 79 percent of the countries for weaknesses in test data protection, and the percentage increased over the period. Listings for lacking patent linkage fell from 32 percent in 2010 to a low of 13 percent in 2014 and have generally risen since then, hitting an all-time high of 43 percent in 2018 (and 42 percent in 2020). Listings for limiting the scope of patentability have averaged 25 percent over the 12-year period, with a gradually increasing trend. In 2020, USTR cited 35 percent of PhRMA-identified countries for issues related to the scope of patentability.

Lack of data exclusivity – or incomplete data exclusivity – was the most frequently criticized. Each year, USTR cited between 47 percent and 79 percent of the countries for weaknesses in test data protection, and the percentage increased over the period. Listings for lacking patent linkage fell from 32 percent in 2010 to a low of 13 percent in 2014 and have generally risen since then, hitting an all-time high of 43 percent in 2018 (and 42 percent in 2020). Listings for limiting the scope of patentability have averaged 25 percent over the 12-year period, with a gradually increasing trend. In 2020, USTR cited 35 percent of PhRMA-identified countries for issues related to the scope of patentability.

Special 301 complaints about compulsory licensing increased over the period. In 2009 and 2010, countries were rarely cited for compulsory licensing, but 37.5 percent of the countries singled out by PhRMA and included in the 2019 Special 301 Report were criticized for policies related to this flexibility. This includes countries that issued licenses, and other countries that amended their laws to streamline compulsory licensing processes.

Notably, USTR did not cite countries for issuing compulsory licenses or changing their compulsory licensing laws in March 2020 in response to Covid-19. These include Israel (which issued a compulsory license for a potential Covid-19 treatment in March); Canada (which amended its law to accelerate the process of compulsory licensing for health reasons); and Germany (which passed a law granting the government more authority to issue compulsory licenses in epidemics).

Was the Special 301 Report Different in 2021?

USTR released last year’s Special 301 Report on April 29, 2020, when it was clear how significant the pandemic would become, but before the brunt of it. The U.S. had almost reached 1 million cases, and shutdowns had just begun.

Between the 2020 and the 2021 Special 301 reviews, the Covid 19 epidemic grew into the major crisis that it is today. As caseloads, hospitalizations and deaths spread worldwide, countries scrambled to access treatments, PPE, and vaccines. Some countries used TRIPS flexibilities to access supplies. Hungary, Russia, and Ecuador issued compulsory licenses for potential treatments as Israel had done earlier. Bolivia sought to import generic vaccines produced under a compulsory license from a Canadian generics firm.

At the World Trade Organization, South Africa and India proposed a temporary waiver of TRIPS obligations to fight Covid 19. Support for the TRIPS Waiver grew, with over 100 countries eventually supporting it. The U.S. eventually announced its support for the waiver as it pertains to vaccines.

Against this backdrop, USTR began the 2021 Special 301 review at the start of the year. Let’s look at how this year’s report was different from previous ones, and how it was the same.

First, the 2021 Special 301 Report did not criticize countries for any IP policies or practices explicitly undertaken to fight COVID-19. This was the case in 2020, and it was the case in 2021 as well. Given the report’s use to pressure countries to cease using TRIPS flexibilities to fight other diseases like cancer and AIDS, this is significant.

The most notable difference in the 2021 Report from recent ones was that Special 301 lists did not criticize countries specifically for compulsory licensing. No countries were called out for issuing compulsory licenses or for changing their laws to make compulsory licensing easier. This is a change from the most recent years preceding 2021.

Overall, USTR was slightly less responsive to PhRMA’s listing requests than in the previous four years. Last year, USTR included 17 out of 24 PhRMA-requested countries in the Special 301 lists (71%). This year PhRMA requested 26 countries to be listed, and USTR listed 16 of them (62%).

On the other hand, USTR continued to pressure countries to drop the use of TRIPS flexibilities other than compulsory licensing. Every country singled out for weaknesses in test data protection last year was singled out for it this year as well. One less country was criticized for lack of patent linkage this year than last, and one less country was criticized for its scope of patentability.

Though they tend to receive less attention, TRIPS flexibilities other than compulsory licensing are important tools for expanding access to generic medicines, and they play a role in the fight against Covid-19. Data exclusivity can prevent the registration of medicines after compulsory licenses have been issued, thus blocking generics from the market. (This would likely be a problem if any country issued a compulsory license and tried to source generics from the EU.) Narrow definitions of patentable subject matter can allow countries to deny patents for new uses of drugs already invented, and many treatments used for Covid-19 are products originally developed for Hepatitis C or HIV/AIDS, like remdesivir and lopinavir/ritonavir. Narrowing the scope of patentability could also reduce the thickets of patents protecting new therapies.

Conclusion

U.S. trade policy prioritizes the advancement of TRIPS-plus intellectual property protection around the world. The Special 301 Report is one of the tools USTR uses to advance this goal. Special 301 Listings from 2009 to the present have consistently targeted countries using TRIPS flexibilities that can expand access to generic medicines.

Over the past couple of years, the global pandemic has led some policymakers to reconsider the balance between intellectual property and the need for access to essential health products for Covid-19. Some domestic laws have been amended, and a waiver for certain TRIPS obligations has gathered support. But this is for only one disease – people around the world would benefit from greater access to all health products.

The Special 301 Reports reflected the need for a better balance of intellectual property rights and access to health care products for Covid-19. In 2020 and 2021, USTR made sure not to cite countries for policies specifically geared to access Covid-19 treatments; and in 2021 it stopped listing countries for the use of compulsory licenses. However, USTR continues to use the Special 301 Report to discourage the use of other types of TRIPS flexibilities that can help countries access generic medicines. A better policy for public health would be to stop citing TRIPS-compliant policies as reasons for listing countries in the Special 301 Report.